Having been in the change leadership business for my entire career I have learned about the many factors that can affect change leadership success. One important lesson I learned early on is that any change leader must be courageous enough to accept uncertainty and yet still courageously pioneer new paths for their organization. In the process of implementing change, the leader’s fear can often manifest itself in the very dangerous personal trait of perfectionism, and this characteristic – the never ending pursuit of purity or flawlessness – can be a major enemy to making change breakthroughs.

To support this viewpoint, I visited a local business leader who knew of our consulting company’s track record in implementing significant improvements in manufacturing operations. He was curious to understand the reasons for our success and also to discuss possible operational improvement programs for their business. In the visit, the President of the company informed me of the ongoing challenges they had experienced in the implementation of meaningful change in their business. Years before they had created a department for managing process improvements in their manufacturing plant and had set up two Six Sigma practitioners as part of that team, but to this date, the organization had experienced little gain from their efforts.

In my follow up visits with the Six Sigma improvement team, I was very impressed with the depth and quality of the analysis they had performed on many improvement projects. When I next asked them why they had not been successful in implementing the projects I was surprised to hear that in spite of the high levels of potential gain, it was rare they could get approval from senior management to implement their recommendations! When asked why, they explained that whenever they presented their findings the senior staff always had more questions and more scenarios to consider. Then the staff would routinely send them back to analyze each of these new options. The end affect was that the Six Sigma team could never remove 100% of the uncertainty in a project so they could almost never garner an approval from the business leaders.

After a few days I finished up my independent assessment of the many obvious improvement opportunities available to the company and then presented my findings to the President and his senior staff. In discussing the various projects in the meeting, I was able to read into their questions, as well as their body language, and they were to a person not comfortable with any unknowns. In that meeting, I experienced the same hesitancy to take risk that the Six Sigma team had described and determined that any further efforts on my part would yield nothing.

It was very apparent that the senior staff was so risk averse that they wanted to insure they knew all of the potential unknowns and expected any proposals to identify all variables and possible outcomes. In this regard, it is almost impossible to ascertain and value all of the possible variables of a change decision. From the point of the view of the Six Sigma team, the senior staff’s never ending desire for perfect information was an easy excuse to avoid the risk of change and was just seen as a delaying tactic. The effect was that the leadership crushed any effort, and eventually any desire, for the Six Sigma team to actually implement meaningful improvements.

For many years I followed the company’s progress from afar and noted their ongoing up and down struggles, which led to multiple changes in ownership and investing partners, all of which was clearly due to their inability to make the obvious and necessary changes needed for their business.

Unfortunately, this scenario is far too common in organizations. Many leaders are so risk averse that they will keep demanding more information in order to put off the requirement to step up and make a decision. This situation then creates a cultural phenomenon that I call “analysis paralysis” that allows leaders to put on the appearances of supporting change but allows them to escape the consequences of a bad decision, or any decision for that matter. What many leaders fail to understand is that their lack of a proactive decision has in effect doomed the organization to wallow in its current state of poor performance, which can threaten its very existence.

How then can organizational leadership learn to move ahead and become risk leaders rather than risk avoiders? Some important points to consider are below:

- Change is an Imperfect Process – There are few change opportunities that arise where all of the variables and outcomes can first of all be identified, and second, can be fully controlled if they do occur. Leaders must accept the fact that even if they can get the majority of the scenarios identified and mitigated there will probably be additional adjustments that will be required as they experience unplanned events and outcomes in the implementation process. Endless planning cannot remove all risk. Effective change leaders must be able to assess the acceptable level of risks and then move the company forward based on the best information.

- Change Implementation May Require Tradeoffs – When establishing objectives for change deliverables it is quite common to attempt to achieve perfection in performance or implementation. However, it is rare in change implementation that there do not arise challenges that require either an incremental deployment or a modification of the original objectives because of unplanned costs or technical challenges. Remember the old adage that “Half a loaf is still better than none” and therefore a partially implemented change may pave the way for the more desirable outcome when resources or technology can support it.

- Change is not an Event but a Process – Almost any change can be broken down into an iterative process so that risks can be mitigated for the organization. For example, a process change can often be piloted in a limited and controlled area, monitored closely, and then methodical adjustments may be made to refine and perfect the process as needed. Once the process is fully refined and validated then it can then be duplicated and transitioned across the organization with much less risk or fallout.

- Move Discussions from ”If” to “How” – Organization leaders need to reframe the discussions of change actions from “if we can justify taking the action” to one of “how can we make the changes necessary to implement the action”. In this case, the leader is taking the position that the change is already supported and the organization now must only figure out the means to a successful end. This is a substantially more favorable position for the company in that it takes the discussion from one of justification to one of implementation.

- Change Participants Must Feel Safe. In order to deliver ongoing change progress in an organization, the leader must create a culture where people feel secure when they are extending themselves to either lead or participate in the effort. Creating this culture will require that the organization rewards both successes and effort, and occasionally even celebrating failures, all of which will reinforce the principle that the organization values change leaders and the improvements they champion.

- Change Mandates the Acceptance of Risk – If the leaders of an organization still find themselves stuck in “analysis paralysis” they either need to draft some risk takers onto their leadership team or engage a credible consultant to help them understand and accept the risk of an improvement implementation. Only then can the organization move ahead.

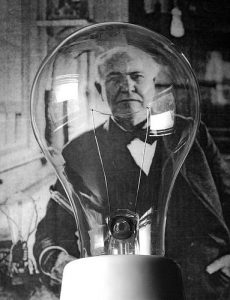

Probably more than any other Thomas Edison epitomized the fearless change leader and modeled the idea that it often takes many failures to finally achieve a meaningful objective. His attitude was one that persistence in the pursuit of change will eventually deliver the desired result. Some of his quotes follow that relate to his attitude on this subject:

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

“Many of life’s failures are people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up.”

“Our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time.”

“Negative results are just what I want. They’re just as valuable to me as positive results. I can never find the thing that does the job best until I find the ones that don’t.”

In closing, in order to create an organization where change becomes a norm, the leader must model the attitudes and behaviors of Thomas Edison and fearlessly embrace the idea that accepting risk of failure is important in the process of driving positive changes.

The author of this article, Kenneth W. Mikesell, is the President of Lean Enterprise Solutions, LLC, a turnaround consulting business that specializes in leading companies through operational and organizational changes. Articles on this and other topics can be found on their website at https://www.bottomlinefix.com .

Comments

Leave a comment